As you read in Part One of this series, Black music and theatre critic Sylvester Russell proposed a "colored company" of the Baum and Tietjens Wizard of Oz in early 1904. As wonderful as his casting ideas were, the producers never pursued the idea.

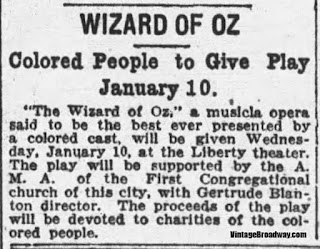

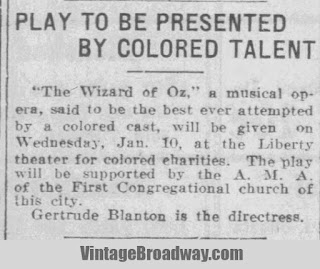

But Russell was not the only Black American to imagine such possibilities. Two days before Christmas 1922, the Chattanooga News announced:

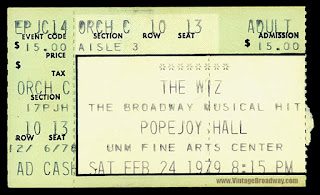

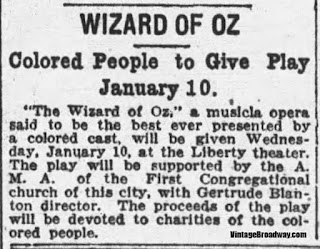

WIZARD OF OZ

Colored People to Give Play January 10

The Wizard of Oz, a musical opera said to be the best ever presented by a colored cast, will be given Wednesday, January 10, at the Liberty Theater. The play will be supported by the A.M.A. [American Missionary Association] of the First Congregational church of this city, with Gertrude Blanton director. The proceeds of the play will be devoted to charities of the colored people.

|

| Chattanooga News, December 23, 1922 |

This production of The Wizard of Oz to be given by "colored people" was the brainchild of Gertrude Blanton. She was Born Gertrude Edwina Lewis, youngest daughter of Albert and Ellen Lewis, on September 9, 1888. The 1910 census reports her working as a musician in an orchestra. In 1912, Gertrude married James Harvey Blanton and they eventually had three children: Dorothy born in 1914; James, Jr., born in 1919; and later, in 1928, another daughter, Caroline. Gertrude continued her musical career as pianist, musical director, and conductor while raising her family.

|

| Gertrude Blanton circa 1930. Courtesy of Richard Davis. |

|

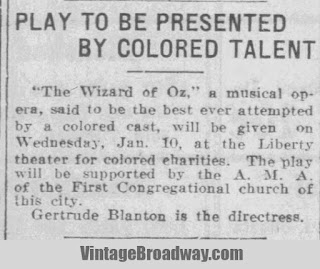

| Chattanooga Daily Times, December 24, 1922 |

Gertrude Blanton had directed one other stage work with students from Howard High called

A Trip to Zanzibar, on May 18, 1922, about six months prior to her staging of

The Wizard of Oz.

There's no information on how or why Blanton came to the idea to stage a Black version of The Wizard of Oz. The original national tour played in Chattanooga four times between 1904 and 1908. I like to think Blanton saw the show and became fond of it. She named her first born daughter Dorothy, too.

Tennessee's "Jim Crow" laws regarding Blacks attending theatre performances were not quite as heinous as many of Tennessee's other forms of repression. According to

Blackpast.org, the 1885 Tennessee statute provided for: "All well-behaved persons to be admitted to theaters, parks, shows, or other public amusements," but the statute also declared that proprietors had "the right to create separate accommodations for whites and negroes." So, Blanton certainly had the opportunity to see

The Wizard of Oz on several occasions when she was a teenager.

No definitive proof has surfaced that Blanton's 1923 production was a performance of the 1903 Baum and Tietjens musical extravaganza, but what else could it have been?

Timing discounts the possibility of it being the Junior League stage version of The Wizard of Oz, which had been written and performed for the first time on December 23, 1922, the same day Blanton's production was announced. The Junior League script had not yet been published and Blanton, not even a member of the Junior League, would not have had access to it.

Advertisements explicitly refer to Blanton's production as a musical opera and musical comedy, and there is no evidence that Blanton, or anyone else, composed a new score. If she, or anyone else, had written a new score, I think it would have been mentioned in publicity. I have also found no evidence that Blanton was a composer.

Blanton was a professional musician, playing in orchestras and bands for at least a dozen years by this point. She would have been conscious of properly acquiring performance rights. I believe that Blanton rented the performance materials for The Wizard of Oz from Tams-Witmark, and what we have here is the first, and so far, only performance of the Baum-Tietjens Wizard of Oz performed by a Black cast.

The Wizard of Oz seems to be the last stage work that Blanton directed. But Blanton managed several small orchestras and bands—one "Colored Orchestra" called the Syncopating Six. They played at hotels, clubs, and dancehalls. The Chattanooga Daily Times reported on June 19, 1932, that "one of the largest dances of the season at Cloudland on Lookout Mountain, took place last evening at the hotel, with Gertrude Blanton and her Syncopating Six playing."

|

| Chattanooga Daily Times, July 21, 1933 |

During this time, she and her husband continued to raise their family of three children. Author Matthias Heyman writes about the Blanton family:

In 1912, . . . Gertrude married another Chattanooga native, James Blanton, and the pair moved in with her parents in their red-bricked house on 320 Cherry Street, situated on the border of downtown Chattanooga, once home to affluent white middle class families, and Ninth Street (on the East Side, now Martin Luther King Boulevard), a “center of African American life in Chattanooga since the mid-1800s.”

The Blanton children grew up in relative prosperity surrounded by a warm and caring family: Dorothy remembers that her parents “always saw [to it that] we had plenty of toys. We had bicycles and wagons and scooters.” The three children playfully called themselves the "three musketeers," and all members of the family were given affectionate names: Albert and Ellen [Gertrude's parents], who continued to live in the Cherry Street house until their deaths, were called Momma and Poppa, their son-in-law, James, Sr., was known as Jim, and their daughter Gertrude as Gert, while Dorothy, Jimmie, and Caroline were referred to as Dotty, Brother, and Tines, respectively.

The central figure in the Blanton family was Gertrude. While James, Sr., helped to make all important decisions, it was she who took care of the day-to-day business of housekeeping and raising the children, as well as caring for both her resident parents. While this would take up most of her day, it still allowed for her actual profession, which was mainly limited to evenings and nights: pianist and bandleader. Indeed, Gertrude was a professional, self-employed pianist who led a first-call small band for “all the local ‘high society’ dances.” “There’s a jump unit known as Ms. Blanton and her Swingsters who walk off with most of the society gigs around the mountain city of Chattanooga,” reported Down Beat in February 1940, where it was revealed that this combo’s leader was indeed the mother of Jimmie, the “sensational […] solo bass man now starring with Duke Ellington’s band.” She may even have been somewhat of a musical entrepreneur. Wendell Marshall, her nephew and future Ellington bassist as well (he was the son of Hattie Lewis, Gertrude’s older sister), maintained she managed about three to five bands in the Chattanooga region, often simultaneously, going from one club to another to make an appearance. Furthermore, the 1940 census lists her profession as a music teacher, so she might have taken in the occasional private student on the side as well.

Through her, music was an essential part of the family: Dorothy learned to play the piano, Jimmie first took up the violin before switching to string bass . . . , and Caroline sang. Gertrude took her children everywhere, including the bandstand, and they would occasionally perform with their mother’s band(s). There can be little doubt that this early experience was of vital importance to Jimmie’s swift rise to professional musicianship.

So, why is Matthias Heyman writing about the Blanton family? Because son, Jimmie, grew up to become an incredible musician—the jazz double bassist Jimmie Blanton. You can read more about Jimmie and Heyman's forthcoming book, Jimmie Blanton. Revolutionizing the Jazz Bass: The Life and Music of Jimmie Blanton—to be published by Oxford University Press— by visiting Heyman's website: www.mattheyman.com

Jimmie Blanton exploded on the jazz scene. On November 19, 1939, Jasper T. Duncan of The Chattanooga Daily Times reported in his "Activities Among Negroes" column:

Another hometown colored boy has made good in music in the east. He is Jimmie ("Kid") Blanton, son of Gertrude Blanton, well known in music circles as an orchestra leader, and who plays for several of the most exclusive dance schools of the city.

"Kid" Blanton, a native Chattanoogan, was taught the rudiments of violin technique by Dr. J. L. Looney, local practitioner, followed his studies through, and is now a member of the Duke Ellington band featured not as a "doubler," but as a violinist, of whom Ellington says, "there is no finer before the public today in the field of commercial music.'

Blanton is on tour with the orchestra at the present time, and has been extolled in musical magazines throughout the country for his outstanding ability.

|

| Jimmie Blanton |

Jimmie Blanton joined Duke Ellington's band in 1939 and through their multiple recordings, transformed jazz and how the jazz bass could be played. While Blanton's recordings and influence live on still, his life and career were cut tragically short. In November 1941, he left Ellington's band, suffering from tuberculosis. His mother, Gertrude, was at his bedside when he died on July 30, 1942, at the age of 23.

* * *

In addition to her family, Gertrude Blanton touched many other lives through her music and musicianship, including all those she cast in The Wizard of Oz back in late 1922.

The morning of Blanton's production of the show, the Chattanooga Daily Times reported that The Wizard of Oz would be performed by "a cast of about sixty performers," with the principal parts taken by students of Howard High School.

|

| Chattanooga Daily Times, January 10, 1923 |

The Chattanooga Daily Times reviewed the performance on January 11, 1923:

"Wizard of Oz" Given.

A very creditable presentation of The Wizard of Oz was given last night at the Liberty theater on East Ninth street by a cast of colored amateurs. Horace Hicks was the Tin-man, and Alonzo Pope, the Scarecrow. The role of Dorothy of Kansas was well played by Dorothy Blanton. Others in the cast were Dave Smith, Minerva Hatcher and Thelma Vaughan. The musical comedy was directed by Gertrude Blanton and a good sum was raised for colored charities.

I spent some time looking into the cast. Blanton's eight-year-old daughter, Dorothy (called Dotty by her family), was cast as Dorothy Gale. The other principal parts were students at the all-Black Howard High School.

Alonzo H. Pope, who played the Scarecrow, was a sophomore at the time. He graduated from Howard High in 1925, attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, and married Louise Marshall. They had two sons, Alonzo, Jr., and Thomas.

Horace Hicks, who played the Tin Woodman, had a fine voice and performed with several "colored" men's choruses.

The only other cast member I could find information on was Minerva Hatcher. Alas, I do not know what character she played in Blanton's production of The Wizard of Oz. But she grew up to have a rich and influential life. Minerva Hatcher was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on September 22, 1906, and almost immediately, the Hatcher family moved to Orlando, Florida.

|

| Minerva's 7th Birthday, 1913. The KKK burned the house a few days later. |

Shortly after Minerva's seventh birthday, the family returned from church to discover their home had been burned down by the Ku Klux Klan. Minerva was sent to live with relatives in Chattanooga.

|

| Minerva Hatcher's high school graduation, 1923. |

Minerva was a senior at Howard High School in 1923 when she performed in The Wizard of Oz. She graduated several months later. She went on to receive a B.A. and an M. A. from Fisk University, the third generation in her family to attend Fisk. She attended Yale University as the only Black John Hay Fellow in Humanities, under the Whitney Foundation, in 1952-'53. Of her time at Yale she said:

I spent the weekdays at Yale, but I'd spend the weekends visiting a friend of mine in Harlem. I told my classmates I could act like a white during the week, but on weekends I had to get back to being black.

Her first husband, Henderson A. Johnson, Jr., was a coach at Fisk. They had a son, Dr. H. Andrew Johnson, III, a dentist. Her husband died in 1954, and Minerva married a second time, to William Daniel Hawkins, Jr., in June 1955.

In 1946, Minerva began teaching at Pearl High School in Nashville, Tennessee. She taught American History and was the senior adviser for twenty-three years. In 1999, one of her former students, civil rights leader Mary Frances Berry, said: "There was a high school teacher, Minerva Johnson Hawkins, who expanded my vision of life, and I feel obligated to try to do the same for others."

|

| Minerva Hatcher - Courtesy of Greg Johnson. |

Minerva died May 18, 2001, in Nashville, Tennessee. She was 94. Minerva's granddaughter said: "She told stories about African-American history you don't read in textbooks."

* * *

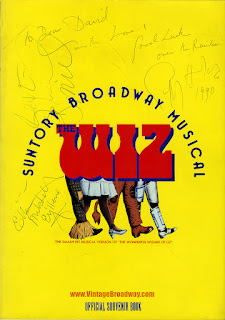

Gertrude Blanton lived until January 1969 and died at the age of eighty in Detroit. Had she lived another several years she would have been able to see the most important Black production of The Wizard of Oz ever—Charlie Smalls and Geoffrey Holder's The Wiz. But, of course, Gertrude Blanton had that idea fifty-two years before they did!

___________________________________________

I extend grateful thanks to Gregory Johnson for both family stories and

permission to share photos of his grandmother, Minerva Hatcher Johnson Hawkins.

And many thanks to Matthias Heyman for information on Gertrude Blanton and her family from his forthcoming book. You can read much more about Jimmie Blanton's life

Photograph of Gertrude Blanton courtesy of Richard Davis. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2022 David Maxine. All rights reserved.