|

| Playbill from 1979 bus-and-truck |

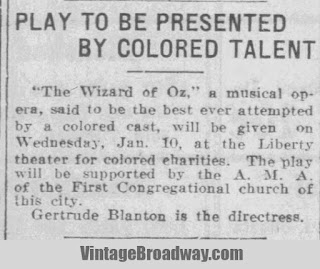

One of the most influential events in my life was seeing the national bus-and-truck tour of the original Broadway production of The Wiz on February 24, 1979.

I had just seen the film version starring Diana Ross and Michael Jackson a month and a half earlier when it had opened in December 1978. I had liked the film version well enough and was playing the double-LP soundtrack album a lot at home. After seeing the film, I started playing the original Broadway cast album a lot, too. And I was now eager to see the stage version, which was coming to Popejoy Hall on the University of New Mexico campus, where all the big touring shows and concerts played.I bought two tickets to the show. I was going to the matinee by myself, and my mom, sister, and I were going to see the evening performance that night.

|

| Ticket stub from The Wiz on tour, 1979. |

|

| Lillias White as Dorothy in The Wiz circa 1979. |

I loved the second performance just as much. I had really never felt "magic" happen on stage before. I don't mean tricks, smoke, and flying monkeys; I mean that the stage disappeared, and I was totally absorbed into the show—like when reading a good book when the words disappear and you're just living the story. It was such an overwhelming experience that I knew I had to be a part of making theatre and to try to make that kind of "magic" happen for other people.

Several years later I began my theatre work as a Production Assistant at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis. In 1984 I was working on Hang On To Me, a musical that was being choreographed by a lovely woman named Carmen De Lavallade (she was also acting in the show). On opening night, I discovered that Carmen was married to Geoffrey Holder, and that HE was coming to the opening night performance!

Geoffrey Holder was the director, costume designer, and artistic conscience of the original production of The Wiz. He was also an actor, had recently played Punjab in the film version of Annie, and was well known for his 7-Up commercials as the "un-cola" man. I mentioned to Carmen that I wanted to meet him, and she said, "Of course!"

|

| Geoffrey Holder backstage at Guthrie Theatre, 1984. |

Carmen introduced us, but they were on their way out to a party. There was only time for a quick hello. I told him The Wiz tour had been what made me go into theatre work. Then Geoffrey Holder signed my Wiz album. I wished we'd had a chance for a longer conversation—but for that I would have to wait several years.

|

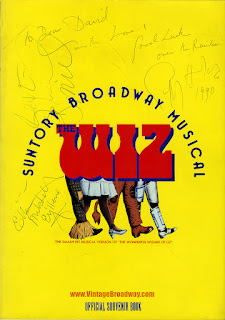

| Souvenir program from Japan. |

Well, number one, that was a whole accident. I met Ken Harper on the street, at Third Avenue. We had dinner. And after dinner at my apartment Harper said he want to do The Wizard of Oz with today’s music—as a television show or something to that effect. It was not a Broadway show at the time. He wanted the bad witch to be beautiful and the good witch to be ugly, someone like Moms Mabley—and Josephine Baker to be the bad witch.

He asked me, “Oh, you would be lovely as the Wiz.” Well, I said, why not? As a black guy, I said I must help him. I should support him. It was a nice idea.

Geoffrey next elaborated on how the show acquired its backers, how he developed the concept drawings and costumes.

[Ken Harper] called me and asked if I’d like to come to an audition. I wore a white suit, being very Geoffrey Holder, just to support Ken.

Now, this old man’s sitting, listening to the music, and Ken Harper only had a little cassette tape. He played the music for this man, and he tried to tell the whole story, how he had conceived the story.

This old man said, “Well, who can play Dorothy? Lena Horne is too old. We don’t have any stars.” In that period nobody ever thought of Motown—nobody ever thought of going in that direction. This old man, the only black he knew was Lena Horne!

I was very disturbed at the presentation. I said, “Ken, when I get time, I will do some drawings for you.”

So one day when I had some time, it was a Sunday, and I drew the Lion, the Tin Man and Dorothy, the Tornado, and all the characters. I called Ken—I’ll never forget this—he said, “Geoffrey, you know I don’t want to come to the west side.” I was on 92nd Street and Broadway, and he didn’t want to cross Central Park! I said, “Ken, find your ass in my house now.” So he came over and he saw the drawings and he freaked out.I said, “The next time you have an audition, show these drawings.” These drawings would erase Judy Garland from their minds. It would erase Billie Burke. All of the images they have of The Wizard of Oz will be erased when they see it done this way.

A couple months later he got a lead to Los Angeles, to Twentieth Century Fox. I said, “Don’t leave without these drawings.” He took the drawings and I think he took Charlie Smalls, or he took his music.

He met Gordon Stalberg, head of Twentieth Century Fox. Gordon Stalberg just loved the music, just loved the drawings, didn’t care for the book—wanted him to work hard on the book. “Why doesn’t Geoffey Holder design the show, do the choreography, direct the show, and play the Wiz? And here is 750,000 dollars. Go ahead and do it.”

It was the first time a major movie company had invested in a Broadway show. It had never been done before. Ken was very happy about the whole thing.

I asked Geoffrey how he had become the director of the show.

I had never asked to direct. I had never asked to choreograph. I didn’t ask to play the Wiz or even design the costumes. I did the costumes as a gesture to support [Ken Harper].

Well, in signing the contract, somebody said, “I don’t see how one man can do everything.” I said, “That’s an insult to my energy!” See, the major directors today have always been choreographers—Jerome Robbins, Herbert Ross, Michael Bennett. You don’t have a choreographer and a director. When you do costumes [too], you save money because you know exactly how the costumes are going to be used; you don’t have to deal with a costume designer who is busy showing his line and has not related to what the book is all about.

They had a clause that they wanted me to have a co-director. I said, “I’ve never heard of a co-director. I’m not in trouble, why would I need somebody to help me?”

And they said, “Oh, we must have a co-director.”

I said, “No no no, I need an assistant director—that’s something else.”

They said, “If you don’t sign the contract, you’re out.”

I said, “Fine, I’m out! I didn’t ask to be in in the first place. May I have back my drawings?”

They said, “Oh, we want the drawings.”

I said, “No no no, those are MY drawings.”

There was a bad conflict about that, because the concept was in the costumes. And they knew that was what Gordon Stalberg liked. I was very broken-hearted, not for the fact that I had to have a co-director. I was broken-hearted because I thought Ken Harper would have stood up for me.

Well, something told me, “Geoffrey, forget it. Resign and just do the costumes.”

“OK, I’ll do the costumes. And I want to speak to the new director”—which was Gilbert Moses, who automatically hired [choreographer] George Faison. “I don’t want him to see my costume designs. I want to know what he has in mind. These costumes were for my direction, for my choreography.”

[Gilbert Moses] said, “How can you make a wicked witch melt on stage? And how can you dwarf men and make them look like Munchkins?”

I thought he had a concept—he didn’t. The man had no vision—no fantasy vision, that is—I’m not knocking his credibility as a director. But he didn’t have a vision for the show.

The show opened and we were in Baltimore, and every time something was wrong, they criticized the costumes. They couldn’t hear the crows sing. “Cut the costumes!”

Mr. Faison wanted to have the tornado coming up like a tarantula. I said, “No, that’s baffling to the audience. A tornado is something that goes up into the sky.”

There were a lot of misunderstandings. We were doing three different shows. The reason why they really wanted Gilbert Moses was so that he could work on the book with Bill Brown. That’s what they wanted him for. When the show got in trouble, they decided to get rid of Moses. Ken Harper asked everybody—he asked Hal Prince, Donald McKayle, Patricia Birch, to direct the show. Pat Birch said, “The only person who has any sort of continuity and some vision is really Geoffrey Holder.”

I was signed to direct the show. There was a lot of bad feeling for me. I was considered arrogant. I was considered grand. And I am arrogant, and I am grand, but I know what I know, and I know what I want.

I got a hundred yards of black silk, and I went and said to the costume lady, “Make me a black bonnet. Attach this silk to the bonnet. Fly that over that trapeze and feed this girl like you feed a microphone, so that she can dance around the house as the house spins.” And that’s how we got the tornado ballet. And we stopped the show within the first two minutes! Gordon Stalberg was coming back to see the show next day, and if I’m going to be the director by then, I needed something new.

Geoffrey and I talked on for another hour at least—about adventures during the try-outs, the publicity campaign, theatre politics, Holder's 1983 revival, his short-lived involvement with the film version, Michael Jackson, and much more.

At one point, I mentioned to Geoffrey how much I loved the brilliant but subtle moment in the show when Dorothy quietly undoes her tight pigtails and lets her hair down while she is singing "Home." Dorothy visually grows-up while singing the song.

Geoffrey seemed pleased I had noticed and remembered that specific detail from seeing the show only twice, eleven years earlier. He said that Dorothy's journey from little girl to young woman during the course of the show was critical. Dorothy had to be a little girl at the opening of the show—and how do you make a seventeen-year-old Stephanie Mills look like a little girl? He explained he had put Dorothy in her best Sunday dress, as if the family had just returned from church and Dorothy hadn't changed into her everyday clothes yet. Dorothy is running around, playing with Toto, risking wear and tear on her most expensive dress, just like any very little girl might. Then Geoffrey casually mentioned his most brilliant touch. He had designed Dorothy's dress to be just a little too small for Dorothy, a little too short. She is outgrowing it! This subtle touch shows Dorothy is a child, wearing an old dress she's becoming too big to wear and that her aunt and uncle can't easily afford to replace.

I had just graduated from NYU's undergraduate design program and would be beginning my MFA at Yale School of Drama in set and costume design in the fall. I don't think I ever got a better lesson in my life in what real costume design could be. Geoffrey had created character, informed the audience of Aunt Em's and Uncle Henry's socio-economic status, gave Stephanie Mills something to play as an actress, and with luck, triggered some strong emotion-memories in the audience—all with a little white dress that didn't fit quite right.

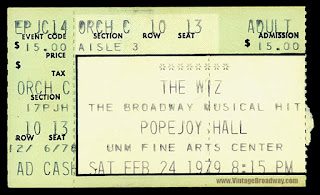

I remember one other thing Geoffrey said that I find most pertinent to this three-blog series about creating an all-Black version of The Wizard of Oz. Geoffrey pointed out that L. Frank Baum, in his effort to make Dorothy a universally identifiable character—an every-child, so to speak—gave no indication in the text of Dorothy's race or skin color. Even W. W. Denslow, the illustrator, had made Dorothy racially neutral by coloring her skin a non-realistic skin color, bright yellow.

Geoffrey Holder's point is essentially the same made by pioneering Black theatre critic Sylvester Russell in Part One of this series. He wrote in his 1904 article: "The [Wizard of Oz] is a budget without race or color . . . It's a something from somewhere that nobody knows anything about." Race doesn't come into play when you're made of tin, stuffed with hay, are a lion, a cow, or a simple little girl, off on an adventure. I've little doubt that this idea informed Gertrude Blanton's decision that The Wizard of Oz was the right show for her all-Black production in 1923.

Anyone can be Dorothy. Anyone can go to Oz.

|

| Advertising poster for cast album. Click to enlarge |

Copyright © 1990, 2010, 2015, 2022 by David Maxine. All rights reserved.